© Davide Padovan

© Davide Padovan

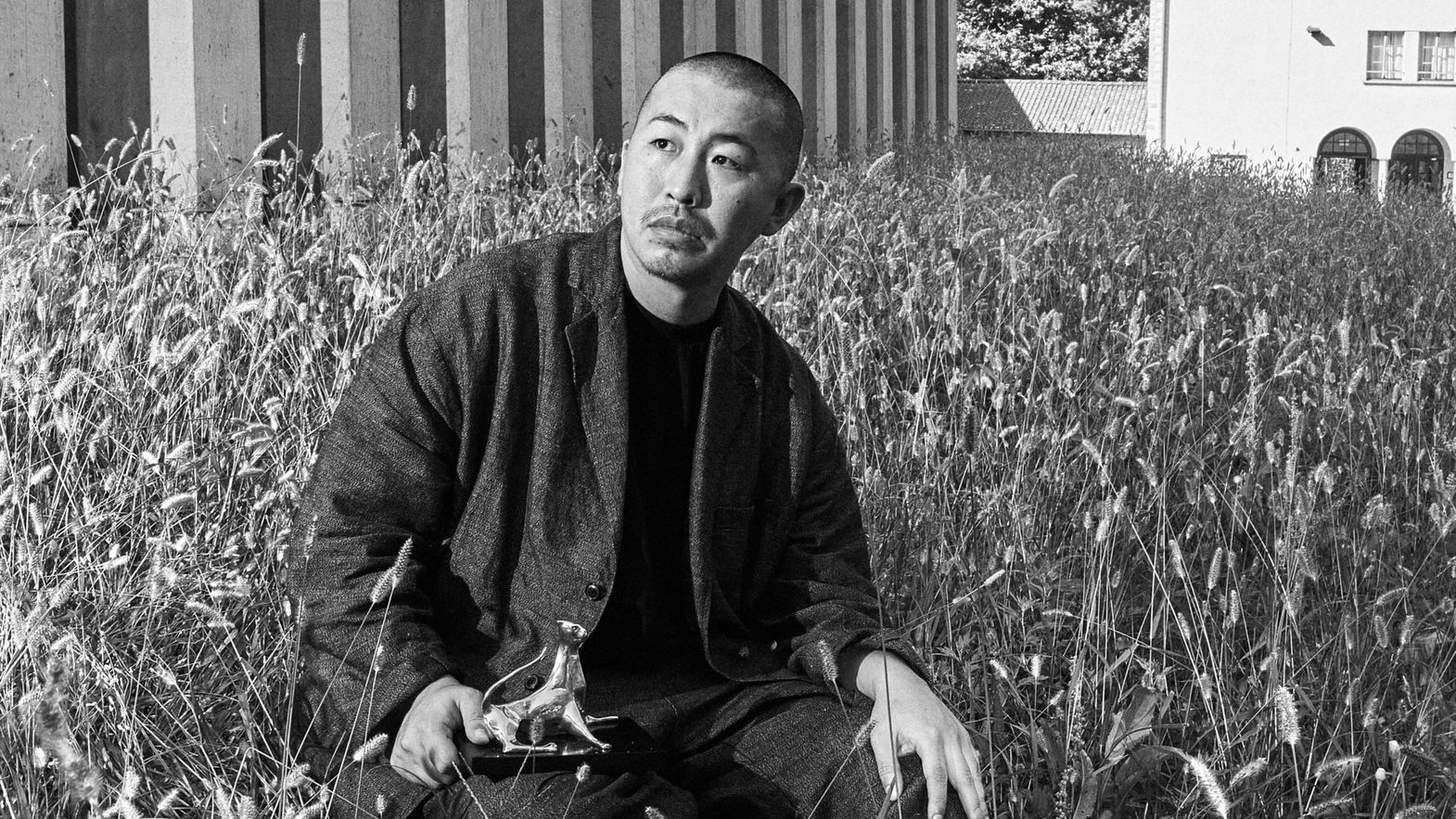

Sho Miyake’s first Locarno visit was occasioned by his feature debut, Playback (2012). He returns with Two Seasons, Two Strangers (Tabi to Hibi), a modern and melancholic adaptation of two stories by seminal manga artist Yoshihara Tsuge: “Scenes from the Seaside” (1968) and “Mr. Ben and His Igloo” (1967). One is a summer tale, the other set in deep winter; both relate a fleeting but oddly nourishing chance encounter.

I wanted to start by asking you about your relationship to Yoshihara Tsuge’s work.

I first read Tsuge’s manga as a teenager, and it felt completely different from any other comics I had read. He pursued a pure form of manga, free from traditional story structures. I was influenced by his way of trusting the reader’s senses and imagination, and his work helped me to rediscover surprise, confusion, joy, humor, and sadness within a dark or absurd world. Like he explored what manga is, I want to explore what cinema is and grasp the essence of life. This film does not simply recreate the manga, but carries on its question: how can we truly feel alive?

© 2025 Two Seasons, Two Strangers Production committee

© 2025 Two Seasons, Two Strangers Production committee

Nevertheless, you do use a stationary camera and a boxy aspect ratio, which evoke the idea of a comic panel.

To observe the river’s flow and be amazed by its magical changes, I believe one must stand still on the shore without moving. A fixed camera can capture even tiny movements, like an actor’s slight smile or the gentle sway of trees. From classic films, especially silent movies, I learned that this sense of wonder is the true joy of watching cinema.

You’re shooting with digital here; this film looks a bit chillier than your last two features, which were shot on 16mm. What did digital offer you this time around?

I still love the flowing grain of 16mm film, but for this story, I wanted to begin in a world that seems still –almost lifeless. At first, the characters are in despair, filled with existential anxiety. Then one day, they see the wind blow, waves rise, snow falls and hear the silence. Surprised by these movements, they begin to feel alive again – as if reborn. To show this journey, digital felt more fitting than film. Also, shooting underwater and in snow was safer and less risky with digital.

In terms of the color palette, the manga is black and white, but I wanted to tell the seaside story under that very vivid light of summer. The second half is much closer to a monochromatic color scheme – and that includes production design and costume design as well. I felt that by not using many colors for the second part, I was able to underscore certain qualities of the protagonist, Lee, who’s played beautifully by Eun Kyung Shim; her sort of texture as a person: how transient she is and how indomitable at the same time, and idiosyncratic too.

To observe the river’s flow and be amazed by its magical changes, I believe one must stand still on the shore without moving.

I did want to ask about casting Eun Kyung Shim. In the “Mr. Ben” story, the protagonist is a male comics artist; in your adaptation, she’s a female screenwriter. She's also Korean rather than Japanese. I was curious those changes – did you made them because you wanted to work with her?

I first met her at the Busan Film Festival a couple of years ago. We didn’t talk much, but I was in awe. She left a strong impression on me – I had never met anyone like her before. It’s hard to explain, but she seemed completely free from any labels or categories, as if she had come from another planet, or perhaps I had. Before shooting, we found out that we’re both huge fans of Buster Keaton. Watching his films, I sometimes sense a kind of “purity” – though I’m not sure that’s the right word. I felt something similar in her. I was also deeply moved that she performed in Japanese, which is not her first language. Standing together between two languages, I wanted to express emotions that can’t be put into words – moments only cinema can capture.

Changing the character’s gender, nationality, and profession helped clarify the theme of two strangers meeting. I came to see not only the significance of making this film in a world still filled with intolerance, but also its more fundamental meaning: I think that filmmaking teaches us to truly see others and to put that into practice. Every decision – such as where to place the camera or how to cut a scene – involves ethical considerations. By respecting others, understanding their humor, empathizing with their sorrow, sharing the joys and hardships of working together, and creating moments slightly happier than reality, I believe we resist the times we live in.

After deciding to make this film with her – I’m laughing because it’s a bit cliché to mention other filmmakers – I was reminded of Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy (1954). To depict postwar Italy, Rossellini chose the perspective of a foreign couple. I found that fascinating. Ingrid Bergman’s character walks through unfamiliar landscapes, her way of moving gradually changing. By the end, she sees her world more clearly. I wanted to portray something similar. The main character and the woman in the seaside story both embark on journeys that help them rediscover themselves and the world around them.

Both stories focus on relationships between people thrown together by circumstance. So does All the Long Nights (2024) and, in a way, Small, Slow but Steady (2022) too. What draws you to these kinds of circumstantial relationships, as opposed to say, friendships or romances?

No one’s asked me this before! Well, instead of predictable dramas or mainstream love stories, I want to explore human relationships that don’t yet have names.

© Davide Padovan

© Davide Padovan